BC to 19th century

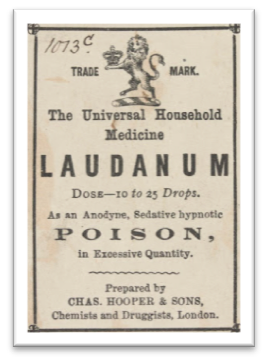

From antiquity until the latter part of the 19th century, alcohol and opium along with cannabis, valerian, and other ancient herbal remedies are used regularly to induce sleep.

From antiquity until the latter part of the 19th century, alcohol and opium along with cannabis, valerian, and other ancient herbal remedies are used regularly to induce sleep.

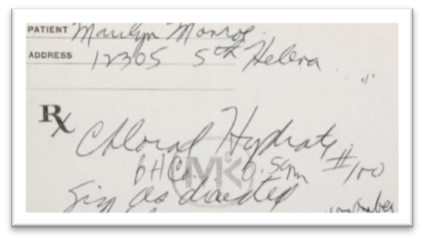

Chloral hydrate and various bromide salts quickly gain popularity. Careful attention to dose is paramount, especially with bromides, due to the risk of overdose with small dosing errors. Chloral hydrate risks (dependence, overdose toxicity, and kidney, heart, and liver damage) are slow to be recognized.

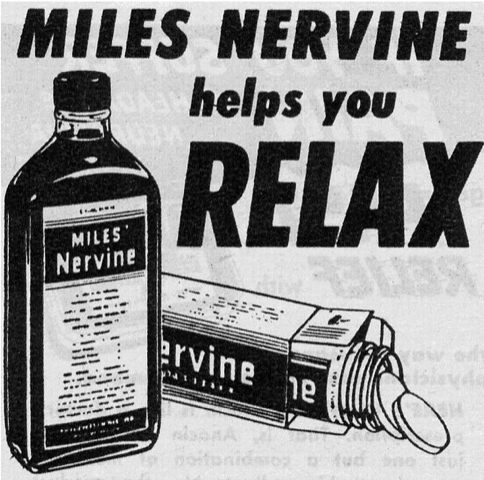

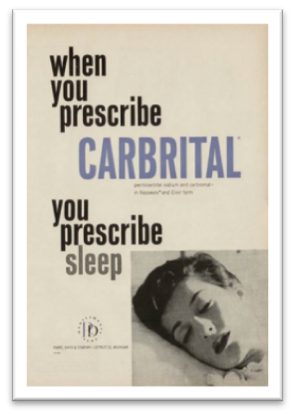

Phenobarbital and other barbiturates are quickly adopted as “safer” alternative to bromides. However, their problems of addiction, withdrawal, and overdose toxicity are quickly recognized. Marilyn Monroe’s fatal overdose involved chloral hydrate and pentobarbital.

With better safety and decades of intense marketing, the benzodiazepines transform sedative use. They, however, do not solve the problems of waning effectiveness, dependence, and withdrawal. Widespread use in older people causes serious problems, including injuries and memory problems.

New “z-drugs” that work like benzodiazepines become the #1 class of sleeping pills. History repeats itself. Intense marketing, widespread use, and same pharmacological effects lead to dependence, withdrawal, injuries, memory problems, and limited effectiveness.

Use of sedating antidepressants (doxepin, trazodone) and antipsychotics (quetiapine) for insomnia jumps up. Many try melatonin, a chemical made by the brain that signals nightfall. Manufacturers patent and develop a new generation of sleeping pills. Efforts to reduce sleeping pill use push ahead.

Use of sedating antidepressants (doxepin, trazodone) and antipsychotics (quetiapine) for insomnia jumps up. Many try melatonin, a chemical made by the brain that signals nightfall. Manufacturers patent and develop a new generation of sleeping pills. Efforts to reduce sleeping pill use push ahead.

A new class of sleep medications called DORAs (Dual Orexin Receptor Antagonists, e.g., lemborexant, daridorexant) becomes available in Canada. Orexin is one of several chemicals in the brain that promotes wakefulness. By blocking orexin, the DORAs reduce wakefulness. This is similar to how antihistamines work. Histamine also promotes wakefulness. Antihistamines block this action in the brain, leading to reduced wakefulness. Early research indicates that the DORAs differ from benzodiazepines and z-drugs in terms of their side effect profile. A unique side effect of the DORAs is sleep paralysis, which is the inability to move or speak for up to several minutes when falling asleep or waking up. Compared to the benzodiazepines and z-drugs, they appear to be less habit-forming, like antihistamines. Their most common side effect is next-day drowsiness.

Important: like other sleeping pills, DORAs should only be considered after behavioural approaches like CBTi have been tried.

What do you know about sleeping pills? Take our Sleep Medication Quiz.

Learn about the various risks associated with sleeping pills.

Learn how Terry gradually reduced and stopped taking sleeping pills.

Learn how to stop sleeping pills safely while getting your sleep back.

It is common for you to experience a return of insomnia when stopping sleeping pills.

Learn how sleeping pills have been used to treat insomnia throughout our history.